Transcribed from the 21 February 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Although we have cut this transcript down significantly less than we generally do, we strongly encourage you to listen to the audio, to fully appreciate the emotional intensity of the conversation.

“The people of Kobanê were about to face a massacre, and the president of Turkey just wore his sunglasses and made macho statements. He exploited the desperate situation in Kobanê.”

Chuck Mertz: We’ve been talking about all the new challenges to the traditional seats of power around the world, from the Islamic State and how it challenges our notion of the modern state, to SYRIZA and how they’re standing up to the Eurozone’s austerity policies, to Spain’s Podemos, who have created a whole new form of democracy, even to the extra-statecraft of free trade zones that exist outside nations’ and a people’s laws.

But there’s something completely unique happening in Western Kurdistan, a new kind of democracy, and it’s led by women, and they are fighting and beating the Islamic State. Here to tell us about Rojava, Kurdish refugee Dilar Dirik is an activist of the Kurdish women’s movement, and a Ph.D. candidate in the sociology department of the University of Cambridge, where her research focuses on Kurdistan, the Kurdish Women’s Movement, and the PYD (Democratic Union Party) which has existed in the Rojava territories since 2004.

Dilar’s blog gets occasionally reposted at the Roj Women’s Association website or you can read it directly at dilar91.blogspot.com.

Good morning in Chicago, Dilar, good evening in the Middle East, wherever you are.

Dilar Dirik: Hello! Thank you. I’m in Amid, but Amid is the Kurdish name for the city officially called Diyarbakır, which is in Northern Kurdistan (Turkey).

CM: No wonder we were having so much trouble getting in touch with you.

So, like when we interviewed Yanis Varoufakis about SYRIZA prior to their winning the election in Greece, and like when we spoke with Jesus Castillo last week about the Spanish anti-austerity movement Podemos, we have to start at the very beginning with this, the very basics, as these are movements that are not reported on in the US media whatsoever.

I have not seen any reporting on what’s going on in Rojava. I’ve seen hardly any reporting, over the last twenty years of doing this show, about even what’s going on with the Kurdish people, what’s going on with Kurdistan at all.

So to start, Rojava means “western” in Kurdish, as in Western Kurdistan. And along the Syrian-Turkish border in northern Syria, there are three areas that are not physically connected to one another—one of those zones, Kobanê, was in the news in January as the Islamic State was fighting for control of that area. Essentially the three zones that make up Rojava in northern and northeastern Syria are de facto autonomous zones.

My first thought about this revolution, Dilar, is that it exists because of a vacuum created by the Syrian civil war. I figure the Syrian government and military was busy, gave up on some areas, and the revolution was allowed to take place. But in fact, the Rojava revolution began back in 2004.

So why did Bashar al-Assad allow it to go on, and what allows it to continue to this day?

DD: Well, Bashar al-Assad did not in fact allow the revolution in Rojava to go on. In 2004, an uprising in Qamishli began, in which many people that took part were arrested, they were tortured, they disappeared in the prisons or elsewhere. Many of them are still missing today. There was a lot of state repression back then.

But it just wasn’t very relevant, because at that time Syria wasn’t very relevant to the world. But also ever since—people have been struggling there for more than ten years—it’s gone largely unnoticed, even by the Syrian opposition.

Basically, what happened after 2012 is the Kurds were able to take over their region after Bashar al-Assad’s forces withdrew—because as you said, they were busy elsewhere, in Aleppo, in Damascus and so on. That was the golden moment for the people to finally seize control over their areas and implement what they had envisioned before.

It’s not right to say that Assad allowed the Kurds to engage in politics all this time, because he simply didn’t.

At that time, too, Syria had very good relations with Turkey and other neighbors. Salih Müslim, actually, the co-president of the PYD, after he was accused of collaborating with Assad—he said to Erdoğan, the prime minister and now president of Turkey: “While Kurds were being tortured and imprisoned, you were having dinner with Bashar al-Assad.” That’s very important to keep in mind.

So even though the 2012 period—and in general the Syrian civil war—has provided a necessary vacuum for this revolution to take place, it still has roots. This ideology that they are fighting with, this collective mobilization and so on, was preexistent. It didn’t just start in 2012. 2012 was a new era, but it certainly was not the beginning.

CM: That’s really fascinating.

You mentioned the PYD (again, that’s the Democratic Union Party). Here in the States, when we see any coverage of what is taking place in Kurdistan, in Syria, in Iraq—whenever there are any fights against the Islamic State, Kurds are said to be winning the battle. For instance the other day I was in email contact with a friend of mine, Patrick Cockburn; he was in Erbil, and I was getting reports from there about how within twenty miles of Erbil, the Islamic State had been held back by Kurdish fighters.

But whenever there’s talk of Kurdish fighters, what’s synonymous with that is the word “Peshmerga.” What do we miss when we label all Kurdish fighters “Peshmerga?”

DD: What you’re asking is very important. It’s also, to be honest, quite difficult to answer, given that right now everyone is propagating this necessary “Kurdish Unity” notion in facing the Islamic State. But the truth is, the Kurds are not united. Certainly not politically.

“Peshmerga” literally means “those who confront death.” And years ago, perhaps decades ago, this term was applied to all Kurdish armed resistance forces that were fighting regimes such as Saddam Hussein’s and so on. Also PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) guerillas were called Peshmerga at one point. But now, that term is usually used for the fighters of the KRG (Kurdish Regional Government) who are paid and employed by the government in northern Iraq, in South Kurdistan.

So when we refer to all Kurdish fighters synonymously, we simply blur the fact that they have very different politics, they have very different loyalties, ideologies. Their only common denominator is perhaps the fact that they are Kurdish—and that they are now fighting the Islamic State. But everything else is different.

For example, PKK fighters are also fighting against the Islamic State, specifically in Makhmur, in Kirkuk, and in Shingal (Sinjar) as well. They played a key role in the rescue of the Yezidi community in the August attack of the Islamic State. But the key difference here is that the Peshmerga fighters of the KRG receive weapons and military support and financial aid, humanitarian aid, and so on—and they should, of course they should—while at the same time the PKK is labeled as terrorist by the same powers.

The fighters of the YPJ and the YPG (the People’s Defense Forces and the Women’s Defense Forces in Rojava) also hadn’t received any support until recently, when the Islamic State launched this major attack on Kobanê. But they have been fighting against the Islamic State for more than two years, and in general for more than three years now. But they were completely ignored. And in fact, not only ignored but also marginalized and excluded.

So there is acute selective empathy. And this has changed, but largely due to the fact that the people in Kobanê have displayed a completely epic resistance. That’s when the sympathy towards them increased. But before that, they were just seen as another sister branch of an organization that is labeled terrorists, the PKK.

It’s very important to make that distinction, because the people fighting the Islamic State in Syria and the fighters in Turkey don’t call themselves Peshmerga. Only the ones in Iraq. Also some in Iran, older armies, have called themselves Peshmerga as well.

I think it’s very interesting to notice the politics behind this selective empathy, and it has a lot to do with ideology. Because the KRG government is also very close to the United States and Turkey, etcetera, whereas those affiliated with the PKK—loosely affiliated, let’s say, ideologically affiliated to the PKK—such as the fighters in Kobanê and in general in Rojava, they have been marginalized because their ideology is radically different. It’s a danger to these states.

I think these are very important issues, and you can probably understand that it’s quite hard to talk about these issues and act like there are no political divisions. Because right now, yes, the people are facing the Islamic State threat, so it’s very important to have a unified focus. But the truth is, ideologically and politically these are very, very different systems. Actually almost opposite to each other.

CM: You know, when I was reading your work and when I was doing research about Rojava, I couldn’t help but keep thinking, who does Turkey believe is their worst enemy, the Kurdish people or the Islamic State?

One thing that was definitely not reported here in the US was when the assault by the Islamic State started on Kobanê, protests erupted throughout Turkey amongst the Kurdish people, who wanted to go into Kobanê and fight against the Islamic State.

Why did the Turkish government refuse to allow those people in? And what does that tell us about the battle against the Islamic State?

DD: I think this is a very important issue. Because if you look at Turkey’s politics towards Syria in general from the beginning, we can actually understand many of the things that are happening at the moment. The ugly truth is that many who say they are now forming a coalition against the Islamic State have benefited from jihadists being in Syria. Because their main goal was to overthrow Bashar al-Assad, and in many cases they didn’t care who was fighting him, as long as Bashar leaves.

Countries like Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey in fact supported—financially, militarily, politically, logistically—jihadists in Syria. We have been saying this for years, but nobody listened. Actually, nobody cared; they didn’t want to see. It was dismissed as some kind of conspiracy theory. But now even US officials say it. And we are just like, well, good morning! We have been saying this for ages now.

“Kurdish women have much better things to do than worry about than what white women in America think about them. The people in Rojava actively oppose capitalism as an economic system. They oppose the premises on which the international order is built, such as the state, such as patriarchy. And they do not believe that women are more liberated in the West.”

And what has been done this whole time? The Kurds were not invited anywhere, to major decisionmaking conferences, the Geneva II conference and so on. So the Kurds were in fact marginalized long before jihadists started getting marginalized—this is very important—not just by Turkey but also by the United States, because of their closeness to the PKK, which of course is labeled as terrorist by the most important NATO ally, Turkey. The second largest NATO army.

So if we consider this and look at the fact that jihadists use Turkey as the main gate to get into Syria; that jihadists—as has been repeatedly reported—were treated in private clinics in Turkey; that jihadists are swinging their swords around in Istanbul, wearing t-shirts of the Islamic State; while Kurdish activists, human rights activists, teachers, journalists, are imprisoned by the thousands in Turkey; we can tell that actually, even though Erdoğan has said, “For us, ISIS and the PKK—and with the PKK the PYD—are the same…”

(He actually said that. He said that the people who are raping and massacring and enslaving the people in the Middle East, ISIS, they are the same as the people who are fighting them in Kobanê. This is actually what he said.)

…Actually, if we deconstruct this statement and look at his actions too, we will see that actually they are not the same to him. Because the PKK and the YPG/YPJ did not receive any support from the Turkish government.

And in fact, in October, while all these demonstrations were happening at the border, when people tried to cross over but they weren’t allowed, and the army actually attacked the people who wanted to go in and fight—at the same time, the Turkish army was able to see with the naked eye the black flag of the Islamic State from Suruç. They saw it, literally, when the Islamic State had advanced so much. But they didn’t do anything.

What they did do is at the same time go and bomb the Qandil mountains, where the PKK are based. Turkey actually went and attacked those that are fighting the Islamic State.

Furthermore, for the last two years there’s been a peace process between the PKK and Turkey. This could have been a moment for Turkey to prove that they are actually genuine about peace with the Kurds. But what did Turkey do instead? They said, “No, we have our conditions for support for Kobanê. Our conditions are that the PYD join the Arab Sunni [Syrian] opposition, that they sever their ties with the PKK, and that they give up any claims to autonomy.”

This is absolutely unacceptable. The people are about to face a massacre, and the president of Turkey wore his sunglasses and just made all these macho statements like that. He exploited the desperate situation in Kobanê at that time.

But he did not expect that all these clashes would erupt. A civil war almost started in Turkey. October was terrible here. I wasn’t here; I was in Europe, and we started a hunger strike there as well. So many, many things happened, in the diaspora as well. And Turkey was pressured into giving up these politics, but not voluntarily.

And actually, we can say that it’s not just Turkey, it’s also all of the other governments who are now forming this coalition against ISIS—had they just listened to the ones that have been fighting the Islamic State for the last two-three years, all of this mess could have been avoided. Those who have been fighting them have been warning about them over and over and over again.

Just the word “ISIS” or “Islamic State” is very new for many people. Many people have only gotten to know this organization since the summer, when Iraq was attacked also, or after August when the massacre on the Ězidis happened. But we have been talking about them for the last couple of years, and simply put, nobody cared, and now everyone tries to act like the hero, but we know who the real hero is and who has been fighting the Islamic State for this long and who has been actively marginalized by the same forces who are now forming the coalition.

CM: Let’s get to the PKK for a moment. The last time we had a guest on the show to discuss the plight of the Kurds, the Kurdish language was still illegal in Turkey, and Turkey didn’t even recognize Kurds as even existing. They denied there were Kurds. NATO—and Turkey is a member of NATO—designated the PKK as a terror group in 2002. In 2008, the European Court of First Instance ordered the PKK to be removed from the EU terror list because the EU failed to give a proper justification for listing the PKK as a terror group. But EU officials dismissed the ruling. Individually, most EU countries do not have the PKK on their terror list, but the UK, Germany, and France do. The PKK has never been designated as a terrorist organization by the UN.

You write, “It is intellectually and journalistically lazy and factually fraudulent to keep calling the PKK a separatist organization, as many news outlets do. The PKK condemned civilian attacks that were committed in their name, declared several unilateral ceasefires, and currently is engaging in peace talks. Even the Turkish state accepts the PKK as a negotiating partner.”

So there’s been a ceasefire since march of 2013, as you were saying. How far would the war against the Islamic State move forward if the PKK were delisted as a terror group by the United States?

DD: Oh! You know, I don’t think I can give a definite answer to this. But I think that would actually be a major solution to many problems that we face.

The terror listing not only means that this organization will not get any military support, it also means that anyone who is trying to raise this issue, even just me talking to you right now—if a police officer were listening to me right now, I could perhaps be put in prison. Imagine that. We’re just trying to engage in a common sense conversation, but this is what the terror listing means. Just a thought crime makes you potentially a prisoner.

And it’s the same in Europe, actually. The criminalization of ordinary Kurdish people in Europe is absolutely insane. Journalists get arrested all the time in Europe. Nobody really talks about it, because it’s taboo. People cannot really engage in legal work, their institutions cannot work properly, they cannot get any funding. It’s just absolutely insane.

“If the people in the Middle East are left alone, if nobody comes and constantly hijacks their dreams and visions and revolutions and their genuine desire to create a better, brighter world, if all these revolutions in the Arab Spring had not been hijacked by foreign forces that supposedly advocate democracy but just wanted to stir up the situation further, this region would be different. It would be the most beautiful place that it could be.”

Listing people as terrorists has a lot of social impacts. It impacts my own research as well. I cannot work properly. Many people cannot work properly. And there are so many people who want to do something, and they have to do it “illegally,” even though everything they are doing is good.

The other problem with this terror listing is it’s absolutely politically motivated. It has everything to do with Turkey being an important NATO ally. The PKK does not pose a single threat to any citizen of the United States. Everyone knows this.

In the nineties there were escalations in Germany, which is why the PKK was listed. This was when Abdullah Öcalan was arrested. People were engaging in some violent acts. But that was very context-related and these actions have been denounced, and it was not like random terrorist violence or anything. It was something completely different.

The fact that the PKK—which has moved away from many of its initial aims, including that of a separate state—is still considered a terrorist organization has a lot to do also with the fact that the monopoly on power and force is in the state.

The violence—the real terrorism in the classical sense—of states such as Turkey against ordinary people who are exercising their rights (given by the same constitution of the same state) is not seen as terrorism. It’s seen as a legitimate use of force. The resistance of the people is labeled as “terrorist” because they are non-state actors. We just worship the state in this global system.

That’s why the terrorist labeling is connected to so many other things. I think if the PKK would be de-listed by the United States, it would first of all be something very common-sensical because the PKK does not pose a threat to the United States of America. But it would also acknowledge that the bigger danger to the US is not the PKK but in fact their NATO ally, Turkey. Because as we have seen, Turkey’s politics actively contributed to the rise of ISIS, and now it is the same people that are listed as terrorists by the United States that are the biggest enemies of ISIS.

So I don’t know, what can be done? These terror listings are so random. Sometimes just one single signature can change everything. And I don’t really believe in terror listings. I do believe that terrorism in the classical sense—irrationally spreading fear and terrorizing people—is a thing, but many states are doing that. Not non-state actors who are often resistance forces.

This terror listing is a huge bureaucratic obstacle to a huge cause, and I could go on and on like this. Because it really impacts millions of people who are just trying to live normal lives, and just one article can label you as a terrorist because of that.

People have to move on and realize that the PKK is not the same as it was before; it is engaging in negotiations, as I said. The aims are not the same anymore. They do not pose any threat to ordinary citizens. Their violence is directed at the state, and actually there is no violence right now—for two years there has been a ceasefire, and it’s just one of the many unilateral ceasefires issued by the PKK’s administration.

So yeah, I think we have to check our priorities when we talk about terror listings, and how much sense it makes to keep the PKK on there. And you don’t have to like them. To argue for the PKK’s removal from these lists does not mean that you endorse the PKK.

CM: So yesterday, President Obama announced that there is going to be an assault on Mosul, the capital of the Islamic State, and that this is going to mean 20,000-25,000 troops in a ground invasion. Let me ask you this, then, because I think this is important; I think this war is more to do about politics than it has to do with military strategy.

What would be of greater benefit in the war against the Islamic State? Sending in 25,000 ground troops and doing airstrikes as the US has? Or delisting the PKK and recognizing the people in Rojava as an alternative that we’re looking for—the alternative that we’re looking for to “offer” to people who might otherwise be attracted by the Islamic State?

DD: Well, there have been several ground invasions by the United States in the Middle East, and we all know the outcomes. One of these outcomes is, in fact, the vacuum that helped the Islamic State to rise. Because when we look at the politics of America and Iraq ever since 2003, we see that the marginalization of the Sunni community there, for example, has contributed a lot to the fact that many people do in fact support the Islamic State.

The post-9/11 islamophobia that was fueled afterwards, and which was used to legitimize the wars in the Middle East, also contributed to the fact that many, many jihadists are now flying all the way from Canada, from America, from European countries, to take revenge on the West. Which is why we also see attacks like the one in Paris, in Copenhagen and so on.

Nobody—absolutely nobody—wants American ground troops in the Middle East. There are many, many forces on the ground, including the Kurdish forces, who can fight and who are willing to fight ISIS. Look, it’s different to go on a mission, to supposedly spread democracy in a place where the context is just so confusing and complicated—that’s different than defending your home.

CM: Let’s talk a little bit about the way Rojava is structured. At the Rojava Women’s Association website where you blog, there’s a story posted from the November 10th International Business Times headlined, “Syria-ISIS Crisis: Kurds grant women equal rights in defiance of ISIS laws. New decree also abolishes forced marriage and honor killing.” The story reports that the local government of an autonomous Kurdish area in Syria has “granted women equal rights to men.”

What do you mean by equal rights to men? Because this sounds great! There isn’t equal rights between men and women anywhere in the world!

“Of course we should acknowledge that it’s incredibly brave that these women are fighting against an ideology that is explicitly enslaving women as sex slaves, raping them, selling them, killing them and so on—these are two quite contrary worldviews, we could say. But on the other hand, why not support the politics of Rojava, the system that is being created there, that is explicitly centered around women’s liberation?”

DD: Well first of all, this whole talk about the West having to “offer” something to the backwards, uncivilized Muslims is completely idiotic, patronizing, dehumanizing, and just incredibly hypocritical given the fact that if it weren’t for Western politics in the Middle East, this region would not be so full of bloodshed. The devastation, the horrible stuff that is happening here, has a lot to do with Western imperialism. I think that is very important to keep in mind.

Also, assuming that Muslims or Muslim communities or anyone who does not live in an advanced capitalist country cannot come up with their own solutions and their own forms of organization of life is just very, very racist.

This news item is actually quite old, and very inadequate. And there was also a columnist on CNN who wrote something very problematic (though meaning to sound very nice or something—I don’t know what her intention was). Basically what she said is, “The Kurdish women who are fighting against ISIS are in fact trying to send us, the West, a message that they share our values.”

No! They aren’t and they don’t. They have much, much better things to do than worry about than what white women in America think about them. First of all, the people in Rojava actively oppose capitalism as an economic system. They oppose the premises on which the international order is built, such as the state, such as patriarchy and so on. And they do not believe that women are more liberated in the West.

“Giving them rights” is also not something that happened recently. Ever since the beginning, since 2012, in the foundations of these three cantons as well, they have gotten rid of polygamy, of child marriage; they criminalized honor killings and so on. This “equal rights” thing was there before.

But the important answer to this is that the women’s movement in Rojava does not think in terms of “rights.” Because there is no state to give you rights. They have learned that the hard way. Rights simply don’t exist. You have to struggle in order to create a society in which social justice and equality are internalized. Who cares about rights that exist on paper and don’t mean anything in reality?

This is a very feudal, patriarchal society, and only with real, meaningful struggle will the mentality of the society change. Turning it into terms of “Oh, look, there’s equal rights here, and on the other side ISIS is enslaving women!” is also very simplistic, and this is not what this revolution is about. This revolution is also criticizing the West. It is also criticizing the chauvinism with which many people are approaching what’s happening.

This is something that’s quite common, I think, in advanced capitalist countries, even among leftists: to look down on revolutions or changes in the Global South, and I think this is very problematic. And even though many of these people are trying to be in solidarity with the people in Rojava, they actually don’t do them a favor by pitting different communities against each other and making it about secularism versus religion or civilization versus barbarism.

No, the issue is much, much more complicated than that. Had it not been for US politics in Iraq, or NATO in the Middle East, or all these other issues that are linked to imperialism and also to ideas and ideals imposed on other places by the West, this barbarism was not possible.

American drones, for example: are they any less barbaric? We have to criticize the entire system in which we live, and that’s when we will see we cannot just make clear-cut divisions between black and white, between West and East and so on, because these issues are very, very complicated.

And if we look at global arms trade, who’s trading arms with whom? For example, the country I grew up in, where I received asylum when I was a child, Germany, has openly and in huge exhibition-style places sold arms to countries like Qatar and Saudi Arabia. All of the villages that were destroyed here in Turkey, those Kurdish villages were destroyed by German tanks. Germany calls itself democratic and opposes any kind of barbarism, supposedly, in the Middle East. But it’s German weapons with which the people here are fighting, both regimes and non-state actors.

These issues show us how hypocritical it is to think in these black and white terms. I think it’s a very easy way to push responsibility away. But I think we have to be honest about it; we have to confront these uncomfortable issues and also realize that if the people in the Middle East are left alone, if nobody comes and constantly hijacks their dreams and visions and revolutions and their genuine desire to create a better, brighter world, if all these revolutions in the Arab Spring had not been hijacked by foreign forces that supposedly advocate democracy but just wanted to stir up the situation further, this region would be different. It would be the most beautiful place that it could be.

But it’s not. Because it’s in nobody’s interest that the Middle East develops. And this is the tragedy of our time, I think.

CM: I want to mention one thing real quick, because we were mentioning stereotypes that the West has of the Middle East, of Arab people, of Muslim people, all the stereotypes that we have. You write about how much the glamorization of the Kurdish woman fighter is distracting the media from the message, from the politics of the Kurdish women fighters.

I think this is also based on stereotypes and sexism and racism towards people in the Middle East, because we believe, in the West, that the Middle East is the most patriarchal society, and that the women are—for whatever reason, even if it’s just the wearing of the veil—subjugated or subordinated and somehow that they like that position, they don’t mind being subjugated or subordinated. But in fact, that is not the case whatsoever.

Why is it not unique, to you, that Kurdish women are leading the fight against the Islamic State?

“The women who have been fighting against ISIS have really been like a rising sun to many people, and I think this will be a much more powerful counterforce than what the Islamic State has done in terms of damage.”

DD: Thank you for these questions. First of all, we do have to keep in mind that this is a very patriarchal region. That is true. There are many different reasons for that, but it is true that in this region women have it really bad. It’s always important to keep that in mind.

But, well, I’m a nineties child, and I grew up seeing Kurdish guerilla fighters who are women. And most Kurdish people in my generation have grown up with this reality. So actually, we would have been surprised if Kurdish women had not been fighting against the Islamic State. Because this had been established as something quite natural in Kurdish politics.

And it doesn’t matter if you support these fighters or if you don’t; the truth is they are there. This, of course, changes your perception of women if you see women who are armed as fighters, fighting against different states. That does a lot with your perception.

It’s also important to keep in mind that the cause of women in places that are perceived as oppressive has often been used by imperialism. “We have to go and rescue the women!” For example Afghan women, Iraqi women. This has always been used to portray this region as a very patriarchal, backwards place, and the West has to intervene and rescue specifically the women.

(And many times, the voices of these women are not listened to. You can disagree or agree with it, but many women do not just measure their level of oppressed-ness by a veil that they are wearing or not wearing. It’s not simple like that.)

In order to justify these unjust wars in the Middle East, women have always been portrayed as these victims that need to be rescued. But then what happens? Why don’t US drone strikes, the airstrikes, the devastation caused in these wars, which have disproportionally affected women and killed women and displaced women—that’s not oppression, or what? The existing patriarchy in this region—justifying unjust wars by that is just absolutely insane.

From an orientalist perspective, seeing women taking up arms against the explicitly femicidal system of ISIS of course challenges very stereotypical prejudiced perceptions of women in the Middle East. But as I’ve said in my articles and as we’ve mentioned here, this is not something that just came out of nowhere, and it’s very disheartening to see that the politics of these women are taken out of the equation.

But the truth is, as we discussed earlier, the ideology of the PKK plays an explicit role in this. The PKK’s ideology is directly responsible for the fighters in Kobanê who are women. I was there, not in Kobanê but in another region of Rojava. I spoke to these women fighters, and I spoke about their media representation as well, and one of them, a commander, said, “We don’t want the world to know us only as ‘the women fighting ISIS.’ And we also don’t want people to know us for our weapons. We want them to know us for our ideas. And our ideas are based on the philosophy of Abdullah Öcalan,” who is the philosophical, ideological representative of the PKK.

This is something a commander of a brigade that is fighting against ISIS in Rojava told me. And you see Öcalan’s picture everywhere. You may or may not like the PKK, but that does not matter. What matters is the fact that these people are fighting with this philosophy. When Kobanê was liberated, they immediately chanted slogans praising Öcalan, for example. You can criticize many things, but at least acknowledge that this is these people’s loyalty. You don’t have to like it; you can criticize this ideology, but this is what it is. This ideology lies behind this resistance against the Islamic State. But nobody wants to know that, because the PKK is listed as a terrorist organization.

Further, taking these women who are fighting against ISIS as this sympathetic enemy against the Islamic State and legitimizing your islamophobia with it by saying, “Oh, look! Islamic State is being hurt by women, ha ha!”—this is also very problematic. Because the fight against ISIS by these women is much, much more than that. It’s really important to listen to what these women are saying, and you will see that you cannot draw it in black and white colors.

Of course we should acknowledge that it’s incredibly brave that these women are fighting against an ideology that is explicitly enslaving women as sex slaves, raping them, selling them, killing them and so on—these are two quite contrary worldviews, we could say. But on the other hand, why not support the politics of Rojava, the system that is being created there, that is explicitly centered around women’s liberation? Gender equality is being taught to the soldiers, to the internal security officers, to the teachers, to the health officers and so on. There is a new kind of alternative society that is being created there.

But that’s also something that people don’t want to see. Even leftists, even anarchists and so on, people who should be in solidarity with what is happening in Rojava, keep criticizing it for not being, I don’t know, “Ideology X” enough. Marxist enough, anarchist enough, feminist enough, whatever. But the truth is that these people are creating a new life there. They are establishing a revolution there. It should be everyone’s task to support this. At least give constructive critiques, rather than just ranting about why they’re not fitting into your dogmatic ideology or whatever.

CM: One last question for you, Dilar, but first I want to make sure that people in our audience know that you, as well as a whole bunch of other delegates, including David Graeber, went to the Rojava area in December. You released a statement on Rojava; our listeners can find out how you can support the people of Rojava by going there.

Okay, so the last question that we do with every one of our guests is the Question from Hell. It’s the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience might hate your response. And I’ve got to tell you, I’m going to hate asking this question.

Do you believe that the Islamic State, because of the way it so horribly treats, rapes, enslaves women—do you believe that the Islamic State can actually bolster feminism in the Middle East and around the world?

DD: I’m actually quite comfortable with this question. I think yes and no. One terrible thing about this is that whenever a huge tragedy such as this one happens, the threshold of atrocity that people can handle changes. Things then start to be measured by the “worst.”

For example, the enslavement of specifically the Yezidi women has traumatized and caused so much damage and suffering to the people in this region. One danger is that from now on violence against women will be measured by these standards, the worst standards. And the worse standards get, the more tolerant we get to it. That’s a horrible, horrible side effect.

But on the other hand, I think it’s not the Islamic State’s specific war on women but rather the resistance which women have shown, specifically in Kobanê, that has changed a lot. It’s changed the terms of what it means to be a woman in the Middle East, I think. Many people contact me just to say how inspired they are, and how this has inspired their own struggles.

I think it’s not the Islamic State’s terribleness but the resistance, the strength, the pride—really, the real sense of pride—with which these women have confronted the Islamic State and showed that a different world was possible, that women can do this and that, that women exist, that women are not slaves, that women have the power to change their status and change the patriarchy in the region…I think it’s the women’s resistance that will change perceptions.

But only if it is accompanied by a longer, endless struggle. Because just taking up arms in times of war and conflict is often just forgotten afterwards. But if we look at the system in Rojava, we will see that all the policies of the people there, the activists of the women’s movement, and the critique of the fighters there, how they talk about the ways their lives have changed, how they’re seen as different now because they have taken part in this resistance—I think this is what will eventually change things. Not what the Islamic State has done.

From what I’ve observed, the women who have been fighting against ISIS have really been like a rising sun to many people, and I think this will be a much more powerful counterforce than what the Islamic State has done in terms of damage.

CM: Well, this morning in Chicago, Dilar, I have to tell you that you are a rising sun for me. I really, really appreciate you being on the show with us, and have really enjoyed our conversation. This really was an honor. Thank you very, very much.

DD: Oh, thank you so much. I’m very happy to be on; I really appreciate the kindness of your show and I really appreciate the conversation that we engaged in. It’s very nice, because I’ve been interviewed a lot recently, and I’m tired of giving the same answers, the same conclusions and so on. That’s why I kind of ranted.

Because I actually just finished interviewing a woman who is a co-mayor in a city here, and she just told me her story. She was married off at fifteen, and then she was a mother when she was underage, and she went through years of domestic violence and now she is a co-mayor of a very patriarchal district here in Diyarbakır. Her story just really, really touched me. When she said this is all due to the Kurdish Women’s Movement, and the Kurdish liberation movement, it was just very inspiring.

And that’s why I’m quite emotionally loaded right now. Because all of these things, the increasing sexual violence here in Turkey, the fight against ISIS in Kobanê and generally in Kurdistan and elsewhere, the protection of Muslims—because this woman was a veiled practicing Muslim, actually—all of these things are linked together.

Just talking to her was very, very emotional, and I’m very happy that this struggle of women like her, who have gone through years of domestic violence and now can be politicians in the public sphere, that this same struggle is now being talked about in a radio show in Chicago. That just makes me really happy. That’s why I thank you for having me on the show.

CM: Well, thank you for being on, and enjoy the rest of your day in Kurdistan. Take care.

DD: You too. Bye, bye.

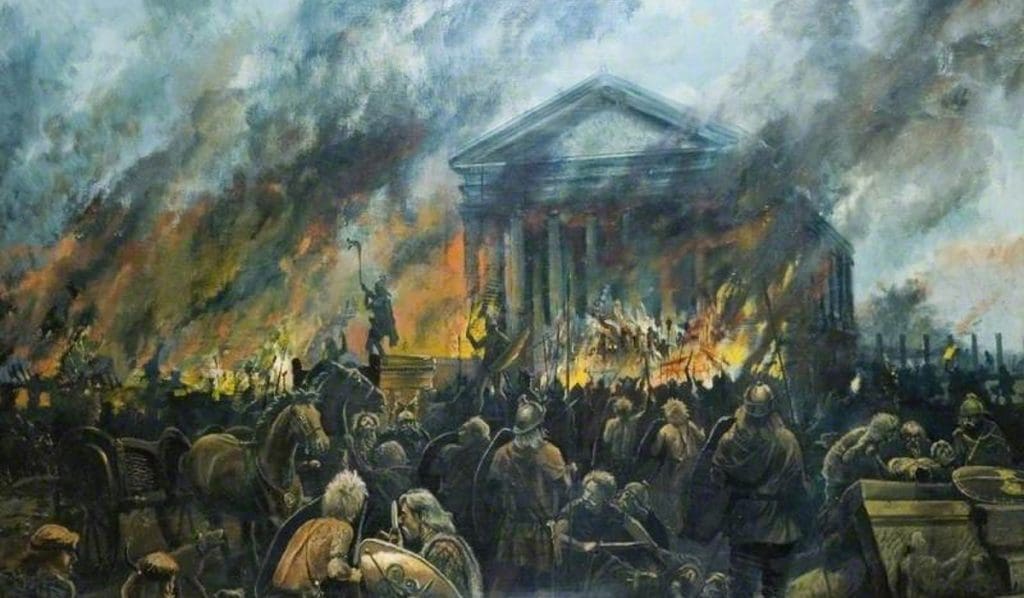

Featured image source: Jin, jiyan, azadî (Dilar Dirik’s outstanding blog).

All other images from a photo essay accompanying another excellent interview, between journalists from Bolsevik.org (the main news and analysis portal of the Turkish Movement for Permanent Revolution, or SDH) and cantonal co-president of Kobanê, Enver Müslim, which appeared on LeftEast earlier this month.